The Magical Art of Block Printing

Woodblock printing is one of the oldest and simplest methods of textile printing, and one that has changed very little over the last few centuries.

It is a slow process which demands precision and patience. The results depend on the skills of the artisans as well as on external elements such as weather, the humidity in the air, and the intensity of the Rajasthani sun at different times of the year.

The prints this craft yields are always beautiful and unique and could never be replicated by machine printing, the little irregularities being reminders of the human touch behind them.

You can learn about our workshop and meet our block printing artisans here

"Block prints are done by eye, and telltale signs of the human hand, even imperfections, are part of the ineffable humanity and beauty of the craft" - Deborah Needleman

We weave our fabrics on power looms in South India. The undyed cloth must first be washed and treated to remove starch and any impurities that might otherwise show after printing. Then, the fabric dries in the wind, hanging on tall bamboo structures.

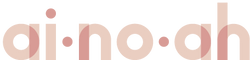

Our artisans carve blocks out of rosewood, also known as sheesham. Rosewood is a durable and sustainable wood native to India. It thrives in the local climate, making it an ideal choice.

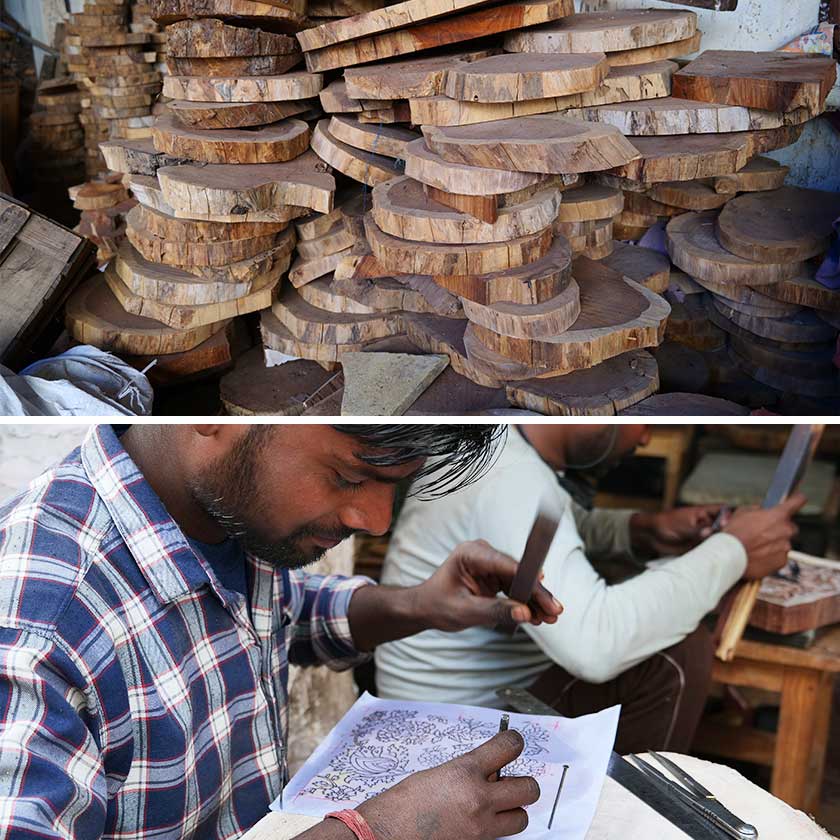

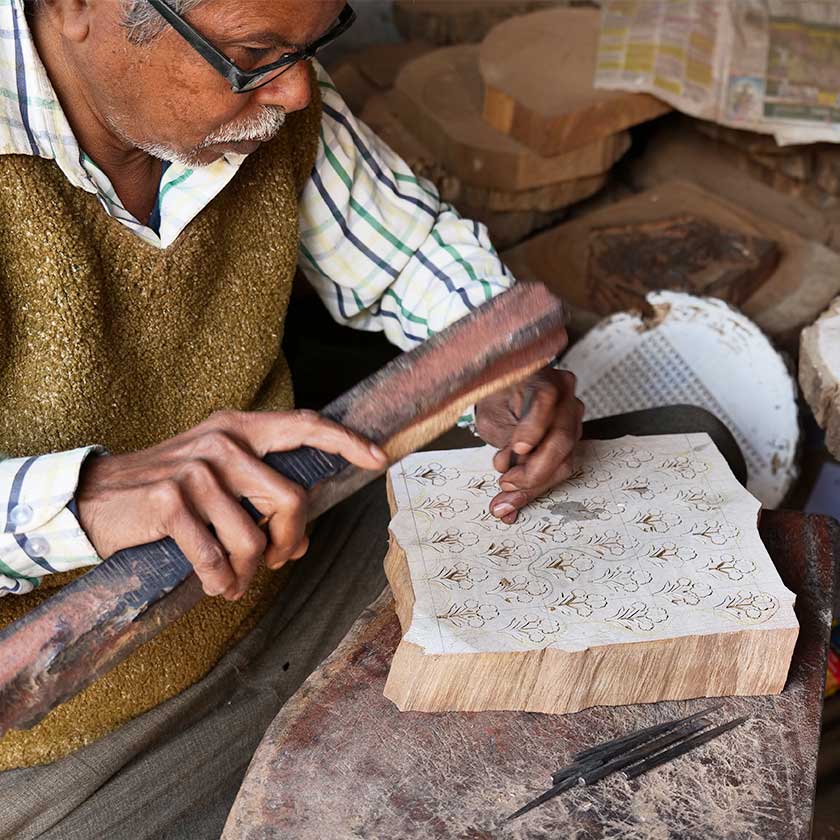

The blocks are sanded smooth and then whitened with a chalk paste which helps the traced design to show better. The carver can now transfer the design onto the block using lampblack or oil.

It takes great skill to create these blocks, usually one per colour, as they must fit perfectly with each other to create a complete design. The designs are carved by hand, without any machinery. Our craftsmen use a series of small chisels, drills and hammers to remove the negative spaces in the design. An intricate design can take six days or more.

After carving, the blocks are soaked in mustard oil for a few days, making them waterproof and preventing the wood from cracking. Tiny holes are also drilled through the blocks to allow the wood to breathe and release any excess printing dyes.

Larger blocks and sections are covered in thin fabric. This is a fiddly but important process that ensures the blocks will pick up the dye paste better, and spread it more evenly when printing, achieving smooth and clean edges.

"The marvel of a hand-printed fabric...Block printing creates identical patterns, seamlessly merging into each other so gently that one cannot follow where the block starts and where it ends" - Vikram Joshi

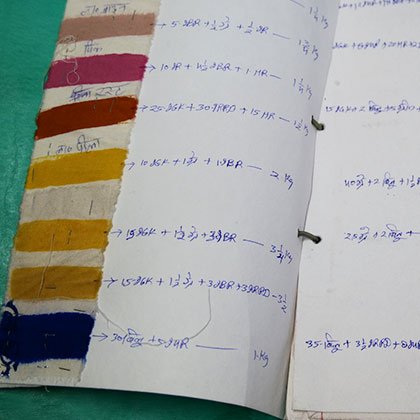

We use a colour process called Indigo Sol, derived from Indigo dye formulas. The problem with cheaper pigment dyes is that they need to be mixed with synthetic binders, resulting in prints that sit on the surface of the cloth, much like paints. Our dyes are mixed with natural gum arabic and go through a process that makes them penetrate the fabric. This gives a softer finishing and ensures good colour fastness.

The true colours do not show while printing; it takes a skilled dye master to mix the right formula to achieve the desired shade.

Printing tables are covered with at least ten layers of jute fabric and a blanket top layer to create a good base which will help achieve a good impression of the block on the cloth.

Before actual printing can begin, the block print artisan, known as chhippa, lays out the base fabric and securely fixes it to the table with pins. A mark is made with chalk and a ruler to indicate where the first block impression should be placed.

The printing trolley is a multi-storey tray on wheels, which can easily be moved from one side of the room to the other. The top tray has a tub that holds the dye paste. A merino wool covered frame floats on its surface, acting like a sieve so that the block only picks the necessary amount of dye.

The printer checks that the dye mix is evenly spread on the tray, and dips the wooden block to coat it with colour. He then presses the block firmly onto the cloth, starting from left to right, and ensures a good impression by tapping it twice with the back of his hand.

If the design contains several colours, the most experienced chhippa is responsible for printing the ground or guide block. Once that colour is dry, another artisan may stamp the next. They repeat this process until all the colours are applied.

Processing the printed fabric in a mild acidic bath reveals and sets the final colour. The photos below show our Ume print during the printing process and after washing.

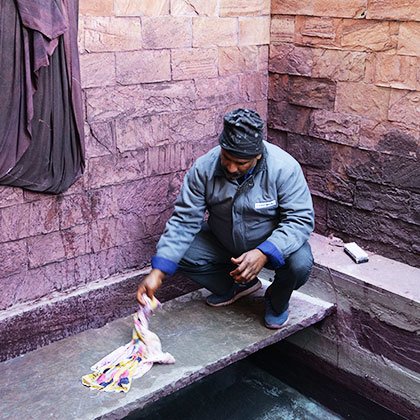

Finally, the cloth is washed four or five times in separate stone baths and finally hung out to dry in the hot Rajasthani sunshine.

Our artisans are at the heart of our brand. These are some of their stories.