The Block Printers of Jaipur

The art of hand block printing is facing many challenges. An industry that was once booming in Jaipur is slowly being taken over by factories trying to replicate hand block prints by quicker methods such as screen printing. The small misalignments and imperfections that naturally occur when the designs are hand-printed are sometimes recreated so that they look like the real thing to the untrained eye.

Block printers faced environmental challenges when they sought to modernise their production in a competitive market. Between the sixties and the eighties they started replacing natural dyes with chemical colours to speed up production. Fabrics were repeatedly washed, which meant that chemicals originating from the dyes would go into the groundwater, making it unsuitable for human and animal consumption in Sanganer and the surrounding areas.

"Here one can truly feel the impact of modernisation ... The pressure to compete in the modern world is taking its toll. Screen printing is a speedier method of printing but spiritual complexities underpin block printing. The chhippa community shares an inherited wisdom stemming from the past" - Suki Skidmore, Sanganer traditional textiles

In 1995, the government released orders to shut down all printing units to tackle environmental issues. About five thousand families' livelihoods and a craft that had been so integral to the area for centuries were at risk.

Vikram Joshi, a local textile historian and owner of a block printing unit, lead a campaign over many years, recruiting other like-minded people such as Pritam Singh from iconic brand Anokhi and the team at Rasa. Together they wanted to find a solution to ensure that a craft that was so close to their heart would not disappear.

They opened the Jaipur Bloc textile park, introducing environmentally friendly production and sustainable labour practices for textile workers. Over six hundred families are now part of the initiative where they recycle used water, collect rainwater, and use solar energy to run the workshops.

We are thrilled to be working with Vikram and his team of artisans on our first collection and to have a partner that shares our vision for sustainable production and ethical work practices.

Our printers have learned their craft from their fathers, uncles and grandfathers. They are proud to keep block printing alive during testing times when fast fashion and a rapidly changing world are a constant threat.

"It is getting difficult to find fine block makers and to source the right quality of wood. More and more children of block carvers are opting out of the traditional family business to take jobs in other sectors." - Vikram Joshi

While designing our first collection, we spent six weeks working alongside these amazing men in the workshop and chatting to them while sharing delicious cups of chai.

Discover their stories here.

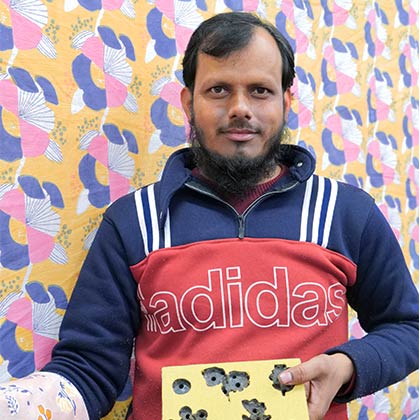

Khurshid, carver

Khurshid is a master carver from Uttar Pradesh, a region with a long history of block printing. When he was twelve, he started learning to carve from his father. He explains how learning to make a simple block can take up to three years. "Once you master the basics , you can attempt more intricate designs."

Khurshid has three children. One of his sons is working as a tailor at the same workshop, whilst the other is pursuing a career in IT. His daughter is at home. He talks passionately about his craft and the pride he gets from his work.

"Block printing will never die. No matter how much screen or digital printing others produce, the quality of block printing will always be unique. The touch of the hand cannot be replicated."

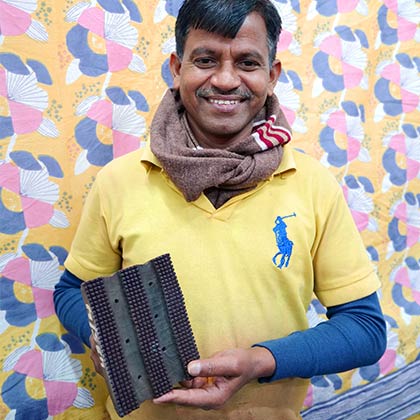

Raju, dhobi (washer)

Raju has the warmest smile. When he is not waist deep inside a stone pool washing fabric, you can find him sitting under the shade listening to his favourite music.

Born in Jaipur, he learned the ins and out of fabric washing from his father, who worked from a set-up at home for various screen-printing units.

Raju's greatest pride are his three children, one has opened a printing workshop, and the other two want to pursue different careers. He explains that the job can be physically demanding. Heavy fabrics need to be washed and lifted as the process involves hand wringing and beating the printed meters against the stone pools to remove any excess water, but he would not do anything else.

Matin, dye master

Matin is from Farrukhabad but has lived in Jaipur for half his life, working as a colour master. His brother's friend had a workshop back home and took Matin under his wing when Matin was a child, teaching him all about colour.

Matching dyes to given colours is done entirely by the eye; it requires many years of experience.

"Block printing is an art and a tradition that provides livelihoods for many local people”.

He talks enthusiastically about the sustainable practises that the Jaipur Bloc has introduced to production methods:

"We all need to make a living, but if our work impacts our life or health in a negative way, then we need to find a solution, and I think this is what the Jaipur Bloc has achieved".

Sailesh, chhippa (block printer)

Sailesh is one of six children. He and three of his brothers have worked as printers for over sixteen years. Sailesh learned the craft from his big brother, twenty-five years his senior, who had learned from his uncle.

He unsure if his children will want to follow in his steps and become block printers, but he is keen that they make their own choices.

His pride in his work is evident. Sailesh hopes the generations to come will continue to learn the craft. "When factories using screen printing methods try to replicate our prints, we feel cheated. Screen printing is not the same. We work with our hands and put a lot of ourselves into the prints".

Sunil, masterji (master tailor)

Sunil is our tailor master and an integral part of the team. He speaks softly, and there is a gentle aura about him.

He has been a tailor at the workshop for ten years.

He was surrounded by textiles from a young age, learning his craft from his dad, a pattern maker, who had a stitching unit at home.

He came to Jaipur from Bharatpur, a couple of hundred miles away. Once he found work, he brought his family to work with him in the stitching unit and now his entire team is from the same village.